Ibn Khaldun writes in the opening pages of the Muqaddimah that “history is a science for which students undertake long journeys of study, which even the idle and ordinary are eager for, from which rulers and grandees seek benefit, and which is desired as much by the uneducated as by the educated.”

While these are clearly positive statements, the following passage shifts tone. He notes that many historians are “parasitic and imitative,” neglecting inquiry into the causes of events, transmitting fabricated reports, and thus turning history into a “diseased pasture” for its consumers.

History carries an apparently contradictory value. On the one hand, past events attract the curiosity of all social strata. We hardly doubt that the past is worth knowing, and in that sense we share a common ground. This interest cuts across social divisions of education, status, and authority. History circulates through everyone’s bloodstream more quickly and fully than most other sciences. It owes its value to this.

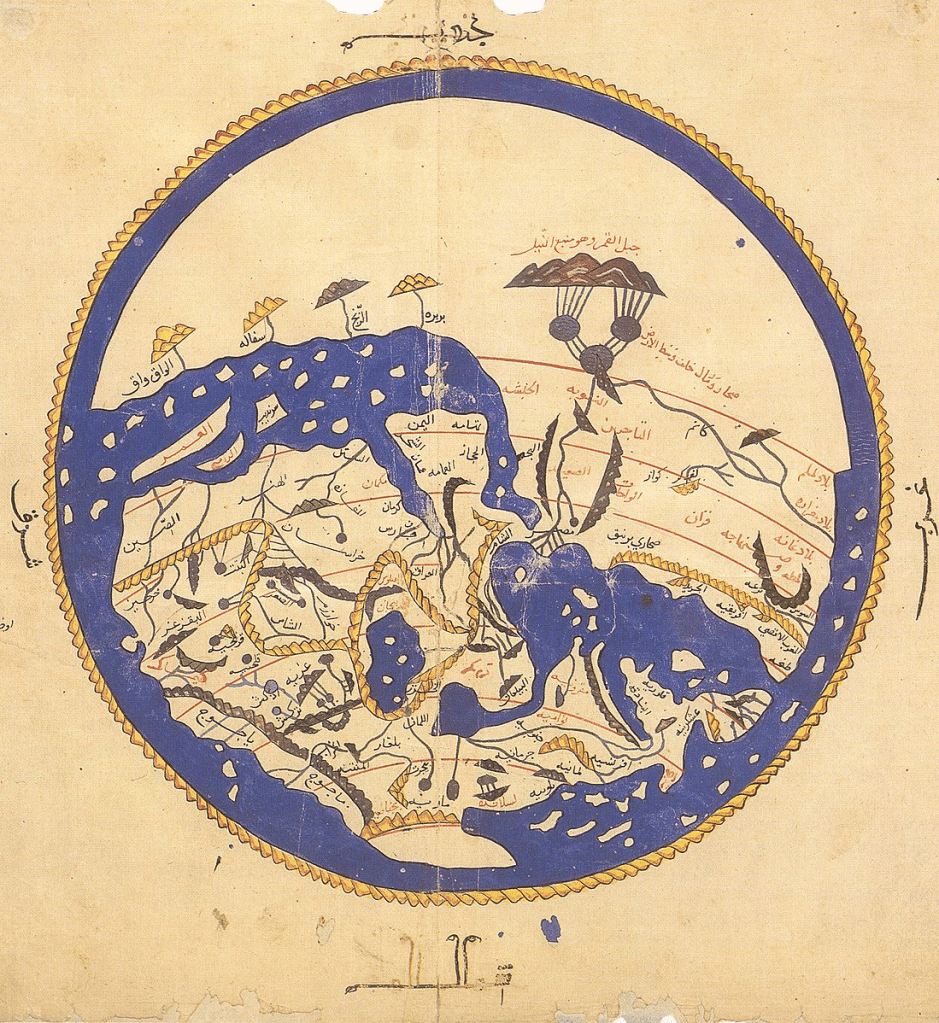

A world map that Al-Idrisi made for Roger II of Sicily in 1154 AD

On the other hand, when historians satisfy everyone’s curiosity by pandering to desire for imitation and entertainment, history loses worth. The historian as producer of history may end up serving this demand for objectified, consumable history. Thus history, at the very moment it fulfills its social demand through mere narration of truth and falsehood alike, loses its seriousness and authenticity. Value flips into worthlessness.

Written in 1377, these ideas remind us that history still enjoys broad public demand today. Without falling into anachronism, we may ask: In Türkiye and other Muslim countries, where does our relation to history fall in Ibn Khaldun’s distinction between imitation and inquiry? What is history today the object of?

The answer can be given in three points:

1. History as a matter of education and employment

If we follow Ibn Khaldun’s method and start from facts, we first see that history has become a large educational field but a modest employment sector. According to YÖK statistics, as of 2022–23 there were 34,145 students enrolled in regular undergraduate history programs. Among 667 different undergraduate programs, history ranks 15th in size. Within the social sciences alone, it is 5th after law, business, psychology, and economics. With distance-learning students included, over 90,000 are currently enrolled in history. Each year more than 10,000 graduate. The total number of academic staff in history is 3,035. YÖK’s Thesis Center lists 12,917 master’s and 3,372 doctoral theses in history since 2010. These numbers rise yearly.

This reveals three massified facts: history diplomas, academic works on history, and employment of historians in higher education. History has become a knowledge-production and transmission object of unprecedented scale. Yet the expansion of education without a parallel expansion in job markets means the degree often fails to secure social position, income, or career. This is part of the broader story of mass higher education in Turkey over the past two decades, which also affected traditional professions like law, medicine, and engineering.

2. History as cultural consumption

Perhaps more than ever, history functions as an object of cultural taste and curiosity. History books and novels remain bestsellers. On television, history is one of the most popular topics of debate, especially late Ottoman and early Republican themes. Of the 3,035 history academics, maybe fifty or fewer are regularly visible on TV, with some producing digital content reaching millions of views. Just as print once circulated historical knowledge widely, today digital media amplifies it further. In Ibn Khaldun’s terms, history is once again “sought after in gatherings of amusement.” We consume history at dinner or on the couch on weekends.

3. History as a field of struggle

This has always been the case. The history of historiography is full of examples of the knowledge–power nexus. In Türkiye, people know that American historical films reflect the self-perception of a hegemonic world power. More importantly, perceptions of the late Ottoman and early Republican eras overlap rapidly with contemporary political debates. Popular history series offer identity models and political role-sets not only for Türkiye but also for Muslim communities abroad. The reopening of Hagia Sophia for worship and, in counterpoint, proposals to excavate the Byzantine Hippodrome under Sultanahmet are both signs that history is a symbolic battlefield.

Across these three dimensions, we encounter abundant history. But the common assumption that quantity necessarily undermines quality does not suffice here. The question is: which qualities are weakened, and how? We live amid an abundance of history but a scarcity of inquiry. History is consumed as livelihood and pastime, as cultural prestige and symbolic contestation, but little is invested in critical examination. We spend (sarf) history without gaining investigation. The word sarf means both “spending” and “exchange of currency.” Change one letter and it becomes israf—waste.

In Türkiye, history as something spent and wasted seems unlikely to be reversed soon. But does this very social consumption not hinder critical inquiry? How can we transform the mass consumption of history into an advantage for investigating history critically and constructing the present? Will history’s turn into entertainment and polemic allow for inquiry into different periods, especially the recent past? For a country that seeks to move beyond being the “parasite and imitator” of the world system, relating to history through inquiry is no longer a choice but a necessity.

July 2024. First published here